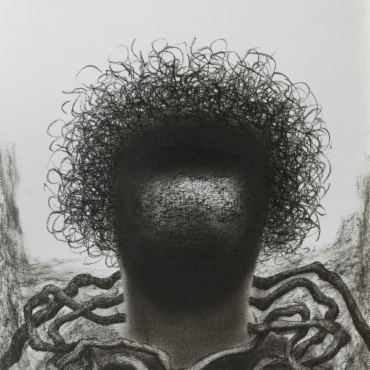

I

Take the name of the locality called Baithankkhana in the vicinity of College Street–instantly rows of paper shops, paper of different variety and printing press appear in front of our eyes. In a suchlike area, Atin Basak was born in the year of 1966. In fact, the form and features of the printing press, the sound it produced or the smell it emitted was quite different when he was born. At that time nobody thought that the introduction of computer would bring about a drastic change to this scenario. And once one has a printing press as his ancestral business, then those zinc letters smeared with ink or the metallic sound of the cradle machine becomes an integral part of one’s existence. During a time of distress, that printing press was shut down. Then the artist was too young to comprehend that the tradition of printing press would have a glorious come back in his life in guise of art–in a newly evolved form. In the world of contemporary print making in India, Atin Basak is surely an artist of significance. As it happens, like others, his journey as an artist was not an easy one. For the aristocratic and affluent families of North Kolkata, it was not easy to shun all the cultures and customs even when their sources of income came to a halt. Besides, it felt awkward to let others know about their privation. This situational stress kept him enwrapped till he reached his age of adolescence. Even during those days of paucity, his awestruck eyes kept on watching how the trams passed through the Harrison Road with their typical rhythm; and it was because of his tram rides he came to know Kolkata intimately. Through the window of the moving tram he observed piled up coconuts at the junction of College Street. After crossing the ‘Dub Patti’ (an area allotted for coconut trade), the varicoloured flower market used to appear miraculously in front of his eyes. Gradually, the ‘phool patti’ (area allotted for flower market) would also disappear from the range of his view. He spent hour after hour sitting aimlessly on the ‘Ramchandra Jenana Bathing Ghat’ (waterfront allotted for ladies) beside the river Ganges. But was this time pass truly unnecessary? Like the course of water, hundreds of thoughts and feelings passed through the mind of the artist. On the way of his return, he often listened to the rehearsal of the musicians of the band parties in their colourful attires. Again, here in this area, huge iron tubs were often seen on roadside where the pavement dwellers used to take their dips. Looking back at the past, the artist found that those huge iron tubs were meant for the horses so that they could quench their thirst. Once it was the horses that pulled trams in Kolkata.

More his mind started shifting away from studies, more he felt the urge to express his surroundings in lines and colours. There was no dearth of encouragement on the part of his family members, but his father got affected by incurable cancer. As those mishaps struck one after another, the artist completed his Bachelor’s degree from the Government Art College and the Master’s degree from the M. S. University, Baroda from the Department of Print Making while dealing with his misfortune. Then his trip to France on scholarship in 2000 added an international touch to his study of Print Making.

What does an artist want to communicate is as important as how should he communicate. Although Print Making serves the purpose of self-expression to a great extent, perhaps Atin needed other ranges as well. Beside Print Making he started trying his hand in tempera by applying colours layer after layer as a mode of his self-expression. And if we ask what he wants to express, that is almost similar to the feelings of most of the artists and literatures–it is to ascertain his own position in the nature.

Demise of his dear granny, closure of the printing press, their ancestral business, terminal cancer of his father, gradual transformation of the city of Kolkata along with its populace, contemporary urban political ambience, the co-existence of the vibrant flower market, strangely clad members of band parties, being fascinated by the architectural patterns of the vintage buildings of Kolkata, enjoying leisure time during tram rides or aimlessly spending time sitting on the quay of the Ganges–the artist whiled away certain phases of his life between these two extremes–his search for his own position between those differences became the theme of his art–either through Print Making or in Tempera. Now, the artist no longer feels the urge to represent the nimbleness of a sparrow lyrically–he rather gets more concerned about vulnerability of the homeless birds perching on the scaffolding of newly-built apartments that have replaced the archetypal old buildings of the city. The transformation of his immediate ambience along with the passage of time rendered him unaffected by the appeal of beauty. Was he more drawn to abstraction or did he set off in search of it? He became more sensitive to the hollowness of the world as a whole characterized by pride and decay. But the variety of colour of the flower market or the multicoloured uniform of the band party still clinged to his eyes–thus, even his prints depicting desolation look so vibrant. Besides, when Atin portrays the varicoloured, mighty faces of the goddess Durga either in print or in tempera, he happens to adore her divine charm. What should we think about it? Should it be termed as usual business venture of the art world? Then one has to defy the impact of Atin’s exposure to the image of goddess Durga since his early adolescence. The image of Durga does not remain an ordinary image of the goddess to Atin but it emerges as his very own goddess. The exhibition of decorative plates (Sara) organized by Debovasha witnessed suchlike portrayals done by Atin.

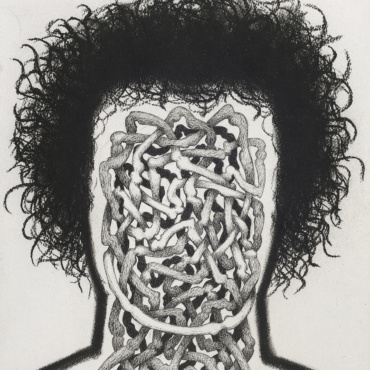

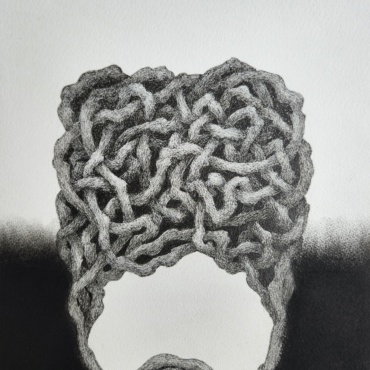

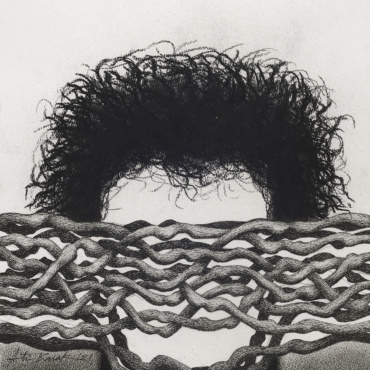

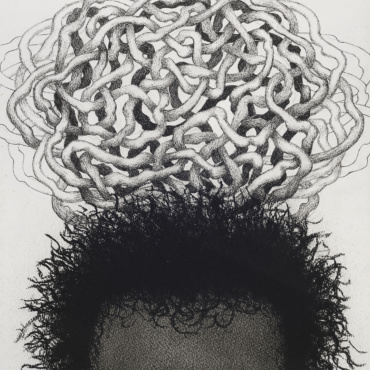

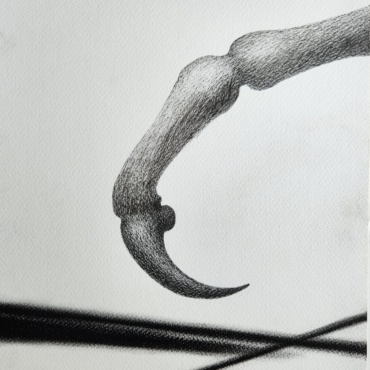

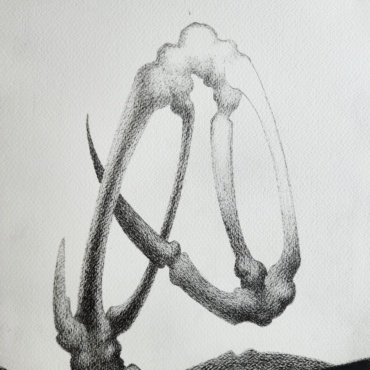

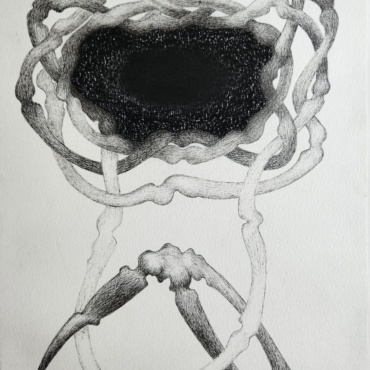

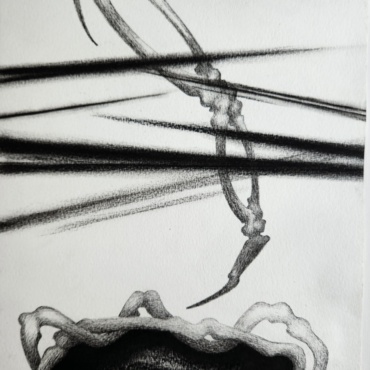

This time, the website exhibition organized by Debovasha displays Atin’s works which are completely different from that of the previous ones. Primarily, they are devoid of colours, done in bold black strokes. The theme of the exhibition reminds us of a Tagore’s song–‘My introspection will never end.’ Here, Atin is found to be absorbed in his own self. The exhibition is named ‘I’.